Even before the end of his rehabilitation at QLI, Shane Hultine had a vision.

Even before the end of his rehabilitation at QLI, Shane Hultine had a vision.

“Nevermind it,” was his vision. Nevermind the spinal cord injury that had made his life so very different. Nevermind the fact that his injury had eliminated the feeling and function below his abdominals. Nevermind what people thought or the perception that he was somehow a different Shane, a lesser Shane, than the person he was years before, the one who didn’t need a wheelchair.

He wasn’t prepared to settle for a life at home. Wasn’t wired to lead a life of quiet complacency, where everyday life under his family’s wings provided something safe. Something predictable.

Instead, when the then-27-year-old Illinois native moved back to his home state in late 2017, he already had eyes on a new venture.

Part of this sea change was motivated by necessity–staircases made his apartment inaccessible, and Shane didn’t plan a return to his previous employer.

But to tell the truth of it, Shane wanted a blank slate. A fresh start.

With seeds planted in other cities, options from which to sprout roots and grow that hopeful new future, he entertained the notion of relocating across the country. Friends in Denver offered a spare room in a new house. And in nearby Champagne, Illinois, he could live with his brother and maintain a stable foundation of familiarity.

But in each of those choices a void remained. Each was a poker hand several cards short of winning the table.

Shane wanted to make this journey his own.

“I had this thought stuck in my head,” Shane says. “Wherever I lived, I wanted to surround myself with people who did not know me from before my injury.”

“I had this thought stuck in my head,” Shane says. “Wherever I lived, I wanted to surround myself with people who did not know me from before my injury.”

“I don’t know how to put words to it. But I didn’t want there to be this inevitable comparison. You know, run into people who hadn’t seen me in two years who would compare me now to who they knew before I was in a wheelchair. That’s an uncomfortable situation for everyone. So I much rather wanted to be in a place where people can only take me for me as I am right now.”

The feeling narrowed his moving options–not because Shane was running from some specter of the past, but because he wanted to define his own success. And he’d already begun to design the framework for that success in one specific location.

That place? Omaha, Nebraska.

During his rehabilitation at QLI, Shane had left behind loose threads in Nebraska. He’d explored preliminary training at Omaha’s DiVentures aquatic center to become scuba certified. He had earned a standing invitation to return to the University of Nebraska’s Department of Biomechanics, where he plied his background in engineering and computer-aided drafting to help model cutting-edge adaptive technologies for the school’s research and development program. And as a QLI graduate, he could offer his personal experience and guidance to rehabilitation clients as an adjunct mentor.

Shane orchestrated the move despite living hundreds of miles away. Coordinating efforts with his QLI team, he identified suitable homes in the community from afar, even watching via FaceTime while QLI clinicians toured Omaha-area apartments on his behalf.

By October 2018, Shane had arrived once again in Omaha. This time, not as a patient in desperate need for healthcare services, but as a driven, independent young man in active pursuit of new milestones and, indeed, a new life.

The threads left behind after therapy quickly became centerpiece priorities. He started with his passion for scuba diving, a passion sparked during his time with QLI’s adaptive sports team.

Although diving represented only one component of his rehabilitation stay, Shane maintained a relationship with Omaha’s DiVentures location well after his move to Illinois. After returning to the Omaha area, Shane began the push to earn his scuba diving certification, something that required not only hours of coursework but an open-water dive in a large body of water.

Although diving represented only one component of his rehabilitation stay, Shane maintained a relationship with Omaha’s DiVentures location well after his move to Illinois. After returning to the Omaha area, Shane began the push to earn his scuba diving certification, something that required not only hours of coursework but an open-water dive in a large body of water.

For that, swimming pools and rural lakes didn’t qualify. Instead, Shane found himself diving amidst the coral reefs of the Caribbean Sea, just off the sun-bleached shores of the Cayman Islands.

Shane’s open-water dive, the culmination of his training, came as part of his participation with the Dive Pirates Foundation, a nonprofit dedicated to funding, training, and certifying, and unifying adaptive divers of all ability levels together for week-long retreats every summer.

It’s a milestone in its own right, not simply a new experience but an achievement opening the door to bigger, more exciting challenges: Shane, now fully certified as an adaptive scuba diver, can move forward with advanced scuba training that will give him expertise in skills like underwater photography and utilizing oxygen-rich Nitrox during shallow water dives.

But Shane’s areas of interest aren’t the only respect in which he’s taken the plunge for new waters.

Shortly after once again settling in Omaha, Shane reconnected with UNO’s Department of Biomechanics, resuming the adaptive design duties he’d held as a volunteer just twelve months prior.

Shortly after once again settling in Omaha, Shane reconnected with UNO’s Department of Biomechanics, resuming the adaptive design duties he’d held as a volunteer just twelve months prior.

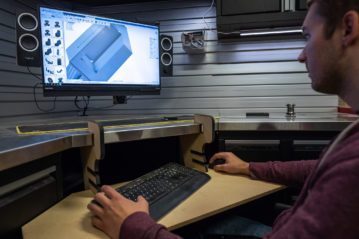

Part of those responsibilities share an overlap with his connection to QLI. Using advanced modeling and 3D printing software, he develops specialized devices worn by the individuals served in QLI’s rehabilitation program. Often, these devices govern functional mobility and stabilization—clever external boots to manage proper gait patterns or assistive tools to strengthen an individual’s hands closing involuntarily as the result of a stroke.

From this point of view, Shane’s experience and perspective build stepping stones, sometimes literally, for those making the journey from injury to independence.

“The technology I’m surrounded by is incredible,” Shane says, his humility outshining any credit he rightfully deserves.

“I think it’s great to collaborate with so many bright minds. We design tools that will make a difference. But, truly, I think I’m the one benefiting most from being there.”

Indeed, rather than maintain a steady course in a volunteer capacity, Shane has pivoted into a new goal altogether—a master’s degree in biomechanics. Encouraged by his UNO colleagues, and in the thick of general courses at the time of this writing, Shane expects to shoulder a full-time graduate-level class load at UNO in early 2020. His two-year program will maximize his impact on the technology and engineering brilliance that’s already changing lives.

Indeed, rather than maintain a steady course in a volunteer capacity, Shane has pivoted into a new goal altogether—a master’s degree in biomechanics. Encouraged by his UNO colleagues, and in the thick of general courses at the time of this writing, Shane expects to shoulder a full-time graduate-level class load at UNO in early 2020. His two-year program will maximize his impact on the technology and engineering brilliance that’s already changing lives.

In short, Shane’s loose threads aren’t threads any longer. They’ve woven into a larger, stronger, more cohesive tapestry. One of his own design.

Shane’s story isn’t impressive because it’s the story of someone overcoming incredible hardship. It’s impressive because Shane has succeeded at living life his way, injury or not.

In fact, in conversation Shane isn’t interested in talking about the trauma of his injury–the sadness and loss on which a layperson might fixate. He’ll look you in the eyes and tell you the truth of it all if you ask. But it’s never long before the conversation eases back to things more relevant. Things more immediate. Things more Shane.

What he’s doing. What he’s making. Where he’s going. He’s more interested in telling you about the parametric modeling used to engineer an upper-extremity exoskeleton than anything to do with his own story. And, in that way amongst many others, Shane represents the truth of all injuries: Identity has nothing to do with a list of diagnoses or the accumulation of injury-related impairments.

Shane chooses to identify himself with momentum, focus, and continued ingenuity. Nevermind all that has been lost. Consider all that is yet to be done.

What Shane Hultine understands better than most is that he isn’t a product of the road left behind. He is now commander, pilot, lone and lead navigator. A man behind the wheel to illuminate the road ahead.