Martin Luther King Jr. Frederick Douglass. Mae C. Jemison. Barack Obama.

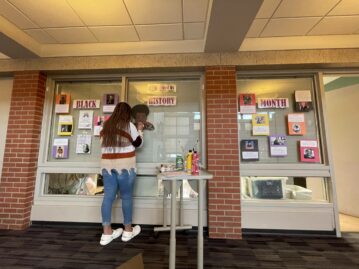

Their names—and the names of many others—adorn the eastern-most windowed wall of the QLI Summit community room, where a growing mural has begun to materialize in celebration of history’s most important African-American leaders. Voices and visionaries all, from a diverse palette of disciplines. Titans of civil rights advocacy, pioneers in space travel, athletes who changed the landscape of professional sports, philosophers and politicians who redefined opportunity in everyday American life.

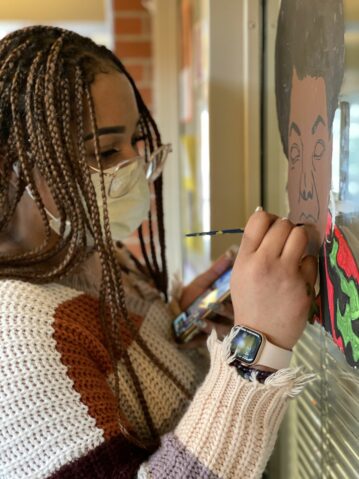

A young woman hovers near the display, standing at the threshold between two interior window panes. With a cart of acrylic paint parked at her side, her phone in hand, she scrolls through a gallery of images of Maya Angelou. Some wheel past in somber grayscale. Others, in full color. One features Angelou flashing a high-spirited smile. A few bear a heavier weight, as if captured after some strained moment of greater concern.

A young woman hovers near the display, standing at the threshold between two interior window panes. With a cart of acrylic paint parked at her side, her phone in hand, she scrolls through a gallery of images of Maya Angelou. Some wheel past in somber grayscale. Others, in full color. One features Angelou flashing a high-spirited smile. A few bear a heavier weight, as if captured after some strained moment of greater concern.

Using careful, deliberate brushstrokes, the young woman silhouettes an image of Angelou on the glass. She rounds the familiar shape of Angelou’s hair, delicately captures the poet’s slightly downturned eyes, traces the faint lines that slope away from her nose and bend under her cheeks.

The painter is LaNeise Latimer, one of QLI’s Active Care Employees who serves the specialized needs of the men and women residing within the organization’s Summit long-term care facility. Quiet and poised, she translates the images in her hand to the window canvas, where vibrant green and orange accents pop against the cream-colored venetian blinds shuttered in the room within.

This gentle humility is familiar to anyone who knows Latimer. It’s the same trait that has helped her garner respect amongst colleagues across the company. Her teammates on the Summit’s C-Wing first and foremost.

They’ve come to know her as a source of resilience and empathy, someone whose subtle gestures have served as a kind of comforting knitwork for her team and residents despite the hardships and isolation of the pandemic. They trust her as a force of reassurance, trust that her penchant for quietude will give her words added power when it is time to speak up.

And they know her for her art.

In the slower moments during a shift—late night lulls when Summit residents sleep or stretches of pause in the mid-afternoon—you can find Latimer pencilling quick sketches. For her, they’re calming reprieves. Little breathers. Ways to recalibrate focus.

In the slower moments during a shift—late night lulls when Summit residents sleep or stretches of pause in the mid-afternoon—you can find Latimer pencilling quick sketches. For her, they’re calming reprieves. Little breathers. Ways to recalibrate focus.

But her art has helped the C-Wing team build a sense of community, too. Last year, as the holidays neared, she co-opted paint supplies from a nearby art and hobby room, carting them back to the wing to transform the windows of its central lounge with cheerful decoration. Like a painting of Snoopy napping on a Christmas light-decorated doghouse, for instance, as though it had been pulled straight from the page.

That artistry became a shared touchstone for her team, transferring a kind of healing property in a holiday season that had turned decidedly unfamiliar, scarily uncertain.

So when a Summit resident proposed QLI dedicate the entirety of one of its campus’s interior walls to the celebration of Black History Month, Latimer’s was the first—and only—name suggested for the role.

“The buzz surrounding LaNeise was that she was a really good artist,” said Mel Mixan, the Life Path Services coordinator for QLI’s Summit facility. “We knew she’d have the care to add extra meaning to this project.”

The commemorative mural, Mixan says, operates as a reflection of Omaha’s—and QLI’s—greater focus on nurturing a strengthened sense of diversity within the community. She hopes it will create pride for the ways in which, at QLI, different backgrounds, ethnicities, skin colors, and worldviews can unite in service of a common mission.

“It’s just one small way to make sure our team keeps the conversation about inclusion top of mind,” Mixan adds, “and, hopefully, a way to help everyone remember that the only real progress to make is the kind of progress we make together.”

“It’s just one small way to make sure our team keeps the conversation about inclusion top of mind,” Mixan adds, “and, hopefully, a way to help everyone remember that the only real progress to make is the kind of progress we make together.”

The mural, in this way, is a reminder of the community’s shared investment in the importance of Black History Month, and in the importance of continuing the long march led by leaders in the Black community.

And it was for this reason—the advocacy of multicultural integration—that Latimer was truly suited for the project. While known for her thoughtful restraint, Latimer’s passion for representation and inclusivity was, for her, a point of pride, an aspect for which she went above and beyond to make her presence felt.

“It came from my grandmother,” Latimer says. “From a very young age, she educated me about art, poetry, Black history. She was the first place I really felt connected to what the people before my time did, how they shaped what we are able to do today.”

Latimer makes a reference to the wall’s faces, its names, but also to the countless uncredited others throughout American history whose brave disobedience against a cruel and targeted system of power has dominoed real change into motion.

“Opportunity had to be opened for people like me,” she says. “They did that. They opened it for us.”

This depth of recognition springs from personal investment. Growing up in the Omaha area, Latimer was surrounded by voices within her family championing active political involvement in the pursuit of social change. Her grandmother, her aunt, the members of her neighborhood church. The list stretches onward, with touchpoints almost too numerous to count. Her family worked alongside former Nebraska Senator Ben Nelson, for instance, helping lay bipartisan foundations for pipelines of financial and infrastructural support meant to reach predominantly African-American communities.

Latimer herself became a voice for the realities faced by African-Americans living in the Greater Omaha area. As a student, she traveled to schools across the city, to healthcare facilities, to other churches, at local events, presenting speeches about important figures and meaningful turning points in Black history—not as a way to help others look backward, but as a way to inspire a new generation to look forward.

That inspiration didn’t stop with education. She made sure to follow through with action, with resolve. Just last year, Latimer volunteered for the ad-hoc United States Senate campaign led by Omaha-based politician Preston Love, Jr., doing her part in spite of the pandemic to stimulate a historic surge of voter turnout within North Omaha. In September, Love became the first major party-endorsed Black U.S. Senate candidate in Nebraska’s history.

When QLI asked Latimer to contribute to the Black History wall, what to paint was a choice all her own.

She thought of her inspiration. She thought of her grandmother.

“We’d always read Maya Angelou together,” Latimer says. “I think a lot about the poem ‘Phenomenal Woman.’ In the middle of all of this education I got from my family about art and poetry and history, I got motivation, too. Her words were motivation to me. I looked up to her work and started writing poems, just like her.”

And so she painted, with Angelou the perfect fit for such a personal addition to the display. Angelou—as a poet, as an author, as an activist, as one of the most important voices in modern American history—challenged how notions of identity could be foisted onto a person because of attributes beyond control. She refused to be defined by heritage, or by skin color. And yet, she unearthed the power found in embracing those same traits.

Latimer paints Angelou’s likeness on the wall not because February is a month of celebration, but because she realizes awareness and tangible, meaningful social action exists as part of a process. Representation, racial inequality, even sheer safety in the shadow of systemic injustice, only improve with continued effort and sustained vigilance.

Latimer paints Angelou’s likeness on the wall not because February is a month of celebration, but because she realizes awareness and tangible, meaningful social action exists as part of a process. Representation, racial inequality, even sheer safety in the shadow of systemic injustice, only improve with continued effort and sustained vigilance.

For QLI, the wall is a way to articulate these very values, not only for its residents and families to see, but for its team to embrace. There is a feeling of united responsibility within the campus walls—a responsibility to do more than celebrate achievement. Indeed, it’s the responsibility to foster a better future.

It’s why recognizing history, in her words, is only the first step.

“People have different ways to see Black history,” she says. “It’s easy to look at February as just a month. For me, Black history is every day. People are paying more attention to it now, but it has always been important. And it always should be.”