“That’s me?” A look of confusion. A collection of images and videos from the past few months is on the laptop screen. An earlier photo is pulled up. In it, her eyes are glazed over and distant, not appearing to recognize the camera, or where she is. She sits in a wheelchair with a slumped posture, head tilted and downward gaze. Over the next few images, a glimpse of recognition starts to emerge. In another, she’s out of the wheelchair and walking with the support of the Zero G device. A tall mirror on wheels is placed in front of her as she makes her way down the length of the Gait Lab. She and her physical therapist pause every few steps and refer to the mirror to make sure her back posture is strong and aligned, and that her legs can be cued to move in a proper rhythm. Her gaze remains distant as they move step by step, and her voice, when it comes, is in a quiet, wavering whisper. She looks up at the mirror at a certain point, but not at herself, but at the camera taking a picture. For just a moment, a small smirk crosses her face. Annika Olson knows that her journey is being documented, and that hint of her personality and humor cuts through into the photo. On the opposite edge of the photo’s frame is her mother Krista, flashing an equally large grin on her face. She knows her fiery and willful teenage daughter is very much present and attentive, even if it is for just a few moments. Krista’s grin too is also one of relief—for the long road weathered and the darkened clouds beginning to lift and start to clear.

few images, a glimpse of recognition starts to emerge. In another, she’s out of the wheelchair and walking with the support of the Zero G device. A tall mirror on wheels is placed in front of her as she makes her way down the length of the Gait Lab. She and her physical therapist pause every few steps and refer to the mirror to make sure her back posture is strong and aligned, and that her legs can be cued to move in a proper rhythm. Her gaze remains distant as they move step by step, and her voice, when it comes, is in a quiet, wavering whisper. She looks up at the mirror at a certain point, but not at herself, but at the camera taking a picture. For just a moment, a small smirk crosses her face. Annika Olson knows that her journey is being documented, and that hint of her personality and humor cuts through into the photo. On the opposite edge of the photo’s frame is her mother Krista, flashing an equally large grin on her face. She knows her fiery and willful teenage daughter is very much present and attentive, even if it is for just a few moments. Krista’s grin too is also one of relief—for the long road weathered and the darkened clouds beginning to lift and start to clear.

__

“We almost considered having her quit,” Krista muses. There’s a period, an almost whirlwind and precocious period in a child’s life that any parent will recognize and anticipate, perhaps with a slight feeling of dread. We lived it when we were children, or we’ve experienced it again from the other side as parents. These newfound passions may fly away in the wind, but there is always the chance that the right opportunity will come along at the right time. For Annika, that experience came when, at the age of eight, she spent some time on her grandmother’s Wyoming ranch, becoming acquainted with horses. To say it unlocked something in Annika would be an understatement. She threw herself into it with intensity. It wasn’t an interest that flamed out, but it grew and grew, ultimately residing in the desire to try her hand at rodeo racing and competitions—what else? She shot just as high as she could.

But if you run into something with such gusto, you might also run the risk of failing at first, and Annika’s parents noticed that. On a particular day of practice, she took some heavy hits and just wasn’t at the level she needed to be. Naturally, the conversation came up that she didn’t have to train for rodeos, but she could still devote her time to riding and caring for them. Annika was adamant—she wanted to keep  training and pushing, even if the going was more than brutal, it was, simply, what she wanted to do.

training and pushing, even if the going was more than brutal, it was, simply, what she wanted to do.

It had worked its way into her dreams and she couldn’t imagine her life without it. “We could see what it did for her, what it meant for her,” notes Krista. “Who would we be as parents if we made her turn away from it?”

So, Annika persisted, building her acumen and expertise, winning competitions, and forging a name for herself in the rodeo community, finishing third overall her senior year of high school. She got a horse—Chicka—who became a constant companion. She went off to her freshman year at Three Rivers College in Poplar Bluff, Missouri, and the early weeks were built not only with the rigor of class introductions but of the prep work and training for her first collegiate-level rodeo competition.

Annika went out riding one afternoon. Sometime later, Chicka galloped back to the stables with frantic behavior. Without Annika. She led coaches out to the field where they were able to locate Annika, down and unconscious in the pasture, having sustained a traumatic brain injury from an unknown cause.

“What if she had quit all those years ago?” It’s a question that has crossed the minds of the Olson family. It’s not easy to admit, but these types of situations may breed the type of questioning, not only why things happened but also what a loved one could have done to prevent it. Certainly, Annika’s passion for rodeo racing and horseback riding led to her injury—there’s no way around that fact. But the same must be said for her passion—there was no way she wouldn’t do those things, and her injury didn’t cast aside those ambitions.

__

“What day is it today, Annika?” asks speech-language pathologist Zoey Bertsch. In front of the pair on a table is a binder, one filled with names and faces of those dear to Annika, while also having an orientation sheet to help provide a daily reminder of where she is, when it is, and why she’s at QLI.

“It is __ [day of the week, month, day, year]”

“I am in Omaha, Nebraska, at QLI.”

“I am recovering from a traumatic brain injury.”

Just as crucial are these kinds of moments where orientation is necessary. In this instance, Zoey provides cueing, throwing out incorrect prompts, starting from the false, to the more accurate, before the true. In the early days, their sessions may have only been these orientation tasks, when, following cueing Annika would repeat the statements, but in a broken, whispery voice. Encouraging cueing for a louder volume would help some, but there would still be something missing. As was the case in her physical therapy sessions—walking with full support in the most absolute sense was without question. Time was what they would have to weather, and though the deficits were significant, it didn’t mean they should set aside their ambitions. Build out the schedule, the involvement, and hone the repetitions, and what comes, will.

should set aside their ambitions. Build out the schedule, the involvement, and hone the repetitions, and what comes, will.

Chief in these goals was reintroducing Annika to horseback riding, which was not only in the realm of possibility but was a core part of Annika’s rehabilitation at QLI from the start. It began with adaptive sports and life path sessions in the Equicizer, a mock horse that clinicians could pair well with devices like the Zero G harness, providing a balance test for Annika. Phase two involved making the journey out to HETRA in Gretna, NE, which specializes in equine therapy. The first time out was peppered in little moments, with Annika completing assessments before getting on the horse—her first time in months back in the saddle. Watching every lap with intent was Krista. There was nothing but joy on her face, but with a restrained quality to it, like a matter-of-fact understanding that this was the fulfillment of one of the biggest goals for Annika following her injury, but one in which deep down, Krista and the rest of Annika’s family and team knew she could accomplish.

“When Annika arrived at QLI she was very dependent on team members,” notes occupational therapist Ellie Messerschmidt. It was a matter in the early days of reengaging Annika as much as possible in her routines, feeding patterns, and therapy sessions. Repetitions naturally provide the avenue through which  great change within a recovery can happen and the same is true for Annika’s growth. When her awareness was at a level hindering her understanding of the importance of certain sessions, it would always be a matter of relating it to her passions and interests.

great change within a recovery can happen and the same is true for Annika’s growth. When her awareness was at a level hindering her understanding of the importance of certain sessions, it would always be a matter of relating it to her passions and interests.

“There were some days early on where she said she didn’t want to do physical therapy,” remembers exercise assistant Andrew Veys. “But after explaining to her the importance of the exercises and sessions and how they relate to her biggest goals, such as a return to walking or riding her horse again, she bought in and wanted to do whatever she could to get a little closer to achieving her goals.”

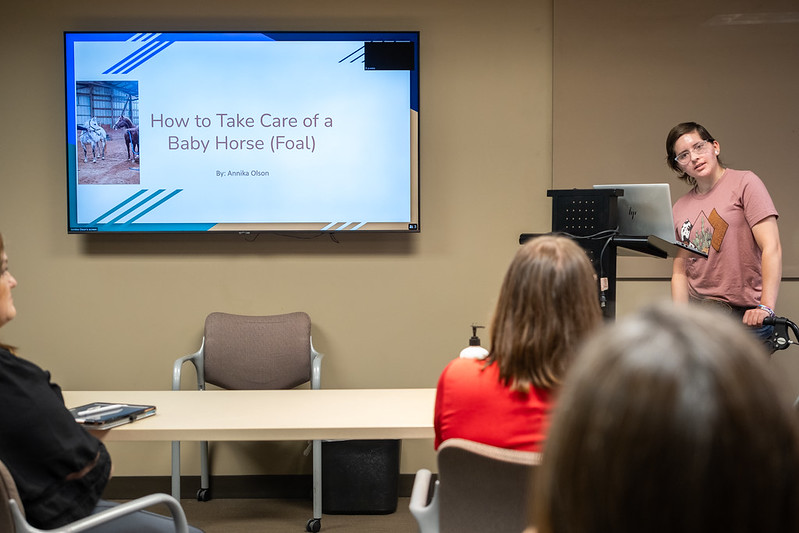

Through it all, Annika’s awareness of her surroundings and recovery was starting to increase and return. Zoey remembers the moment when everything began to click as a session in May 2023. “Music was a very important part of Annika’s life,” she says, and no song is perhaps more resonant with her than Gwen Stefani’s “Hollaback Girl.” Zoey would play the song, cueing Annika to join in, saying the last “–girl” with as much gusto and enthusiasm as she could. In that session, Zoey knows as it is the moment when “Annika’s voice turned back on.” Previously, Annika’s family had mused the possibility of purchasing a voice amplifier—all it took was the time and effort. So too did the perception of what the journey would take before change was visible. Now the command of herself and her future has grown to new heights. Not only will she be returning home to ride Chicka again, but she’ll also be navigating the care of Chicka’s foal.

journey would take before change was visible. Now the command of herself and her future has grown to new heights. Not only will she be returning home to ride Chicka again, but she’ll also be navigating the care of Chicka’s foal.

While preparing for a team conference, Annika and Zoey looked through the series of photos and videos that documented her journey moment by moment. Annika nearly couldn’t recognize herself in such a state, early on in the recovery. Thinking back to those times when things were different adds fuel to the fire for Annika. There’s a mantra adopted early on by her family that Annika has taken to repeating constantly “kicking ass, every damn day.” Always said with a smile and laugh, but a reminder to herself, even in the moments of tiresome work, that she continues to do as she says.