“I’ve always believed you have to find ways to live the life you want to live. Not your parents’ life, not life under the influence of anyone else or anything else or the things you see on social media. You have to create the life you want.”

Abraham “Abe” Stubbs set out to create that life, chart his own course. He started with a purchase. $800 spent—”impulsively,” in his words— on a new kayak and all the gear necessary to be gone for days. Life jackets, paddles, waterproof rucksacks and the food they carried.

This was self-reliance. This was the start of something new, something entirely individual. It slowed the pace of the big city and silenced the noise of social media and eased the stress of time on the job. It was a way to breathe in the fresh air, a way to remind himself who he was at heart.

This was self-reliance. This was the start of something new, something entirely individual. It slowed the pace of the big city and silenced the noise of social media and eased the stress of time on the job. It was a way to breathe in the fresh air, a way to remind himself who he was at heart.

The first day, Abe and his older brother nosed down Iowa’s Raccoon River for six hours. The second, after camping overnight on the shoreline, they kayaked for another four.

Abe had found himself. Every moment drifting on the current under the sun, or cutting into the water with the edge of the paddleblade, a moment of freedom. It was a freedom he’d created, the sort of individualism he lived for. He’d kayak every weekend for the rest of the summer. The impulse purchase had dovetailed into a life-changing passion.

At the time—June 2017—the resident of Waukee, Iowa, oversaw drywall projects and repair jobs for a local construction company. He was 19 years old and already one of the company’s standout employees, having acquired a battery of skills through months and months of trial-by-fire experience.

Yet his was not a simple job. Nor an easy one, despite his expertise. Through August and September Abe committed long, physical, demanding hours exclusively to the company’s countless contracts.

“I was sleeping well and eating fine,” he says in retrospect, “but I was just so exhausted.”

In telling his own story, Abe notes one date: September 27, 2017. That morning, through a haze of exhaustion, he and a colleague took a company truck on Iowa’s Highway 44. Westbound, toward the next of many jobs.

“I remember waking up in the opposite lane with my coworker trying to grab the steering wheel, just shouting my name.”

Abe had fallen asleep behind the wheel for only a fraction of a second—long enough to lose control, long enough for the truck to skew toward oncoming traffic. Startled by his colleague, Abe attempted to swing the massive vehicle back into the correct lane. One of the truck’s tires exploded mid-turn. The wheelrim bit into the road surface, throwing the truck into a roll. Its immense, spinning frame toppled off the highway into the adjacent ditch, finally stopping at an oblique angle on the slant of the hill, wheels facing open sky.

It was 10:15 A.M.

Fully conscious for the crash, Abe felt only excruciating pain in his neck. He couldn’t move anything below his chest. While his coworker survived and escaped the vehicle, Abe was trapped. Upside-down, pinched at the thighs between the steering wheel and the seat, which had been crumpled together by the force of the wreck, he hung suspended for the better part of an hour. Emergency response teams arrived, but found themselves unable to extricate Abe until they sawed the truck cab apart and pried it open with hydraulic rescue equipment.

A full calendar month of hospital treatment and trauma care passed before Abe learned the scope and severity of his injuries: a broken neck at the C6/C7 vertebrae. The injury left him with catastrophic impairments through his torso and all four limbs. He was quadriplegic.

“For a long time I thought I would just take a few months to heal. Go back to work and everything would be fine,” Abe says. “I thought that I’d be able to walk or use my hands again.”

Instead, in a wheelchair, his hands unresponsive to commands, Abe faced an alien and unwanted feeling: dependence. The freedom he’d felt on the riverfront—sovereign over his vessel in the current—was gone. Now, everything required help. An extra hand. Someone else to do it for him.

While participating in acute rehabilitation, he relied on assistive tools to perform rudimentary, functional tasks. Cuffs to slip his hand into just to hold his phone; leg loops around his thighs to lift and reposition his legs during basic transfers. He could bring his arms up against gravity but lacked the coordination and strength to complete basic tasks without help.

It was a suddenly reliant life. It was constant frustration.

“When I was 10, my dad would let me drive his truck around in Mexico,” Abe says.

“By 12, I was helping him with things around the house, helping him with groceries. I was in charge of paying my own phone bill. My whole life I’d been free to do things on my own. All I wanted was to be able to do all this myself again.”

Abe recalls not wanting to pursue additional rehabilitation at QLI. For him, the prospect of another four months in continued therapy—in an inpatient healthcare center hours away from home, no less—seemed unreasonable compared to the allure of returning to the aspects of normal life. A familiar town, a familiar living space, his family, his girlfriend. He wanted to pick up where he’d left off, hit “play” on everything the crash had paused.

But Abe saw hope in one aspect of QLI’s program: adaptive sports.

“It would mean the world to go kayaking again,” Abe says, admitting adaptive sports represented the deciding factor that convinced him to come to Omaha. “That motivation was huge for me.”

He arrived in January. Immediately, his clinical team blocked out a schedule dense with exercises and training relevant to Abe’s goal of returning to independence. Through the winter months, he worked at almost every hour of his waking day on countless skills and muscle groups—functional training with occupational therapists, intensive strength and mobility training with QLI’s physical therapists. With his residential team, he plied the gains made elsewhere on simple things, sometimes tasks as focused and granular as learning how to manipulate a fork or learning how to put his long hair into an easy bun or pony tail.

At the outset, he felt a culture shock with QLI. The first day, a physical therapist instructed Abe to transfer both his legs to a mat roughly the height of his wheelchair without help or tools—something Abe hadn’t accomplished since his accident.

“I tried to tell [the physical therapist] I couldn’t do it,” Abe says. “But they completely believed I could do it without the loops.”

With coaching and pointed direction from the physical therapist, the process took more than 30 minutes of pivoting and repositioning and struggled hoists before Abe successfully moved his legs from his chair to the mat.

But he’d done it. And that was the goal, no matter the time. Whether it took 30 minutes or three hours—create success by any means necessary. Create independence.

At the time of this writing, after six months with his QLI therapy team and hundreds, if not thousands, of repetitions, Abe can accomplish the same task in fewer than 20 seconds.

His entire rehabilitation program at QLI is a collage of this effort and escalating efficiency, moment after moment of clinicians working Abe to the point of failure, and guiding him even further beyond. Despite arriving needing assistance for even the simplest of tasks, Abe eventually rearmed himself with enough functional ability—improved grip, arm, and core strength—to manage all of his daily needs without the help of others. These weren’t simply drills in a gym or a sterile therapy space. These were skills that increased the quality of his life.

After four months at QLI, Abe graduated to a simulated apartment, a realistic living space on QLI’s campus where his level of external support was greatly, if not entirely, reduced. Here, practice became perfect. The benefits he’d gained from therapy saw real use in situations he’d navigate in everyday life. Brushing teeth, preparing meals, transferring into and out of bed or the shower.

But unorthodox problems presented themselves as well, problems for which Abe would have to flex his unique creativity to solve.

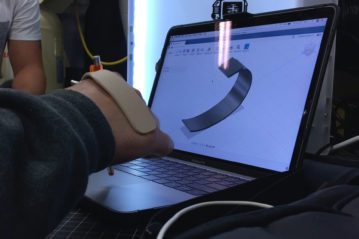

With his hands still impaired, he found it difficult to pull charging cables from his phone or his laptop. To mitigate the issue, he designed a simple, hard plastic loop to affix to the cord itself, through which he could hook a finger and pull with the muscles in his arms. After purchasing a new compound bow for a growing interest in archery, Abe struggled to close his hand around the riser, despite his shoulder and biceps growing strong enough to steady the bow and pull the drawstring. Abe and QLI therapists recorded a series of hand measurements and used his familiarity with computer-aided design to sculpt a specialized cuff to mount to the bow itself. This, plus a unique chin trigger Abe had found and implemented himself, allowed him to fire arrows with gratifying autonomy—and shocking accuracy.

With his hands still impaired, he found it difficult to pull charging cables from his phone or his laptop. To mitigate the issue, he designed a simple, hard plastic loop to affix to the cord itself, through which he could hook a finger and pull with the muscles in his arms. After purchasing a new compound bow for a growing interest in archery, Abe struggled to close his hand around the riser, despite his shoulder and biceps growing strong enough to steady the bow and pull the drawstring. Abe and QLI therapists recorded a series of hand measurements and used his familiarity with computer-aided design to sculpt a specialized cuff to mount to the bow itself. This, plus a unique chin trigger Abe had found and implemented himself, allowed him to fire arrows with gratifying autonomy—and shocking accuracy.

Even his new pickup truck, whose adaptive hand controls he learned to use with the help of QLI occupational therapists, was the object of Abe’s constant ingenuity. He consulted with designers to install a hoist-style crane lift in the pickup bed, and himself engineered a key extender to more easily access the vehicle’s ignition.

As Abe’s operational skill with computer-aided design increased, he and QLI’s Life Path Services team joined regular training sessions at the Department of Biomechanics at the University of Nebraska Omaha. Abe’s designs were fine-tuned, tweaked for maximum effectiveness, and manufactured via a 3D Printer. Where similar modifications would often cost hundreds of dollars through third-party vendors, Abe authored his own independence with sometimes as little as 90 cents of hardened filament.

His passion for clever design had opened an unexpected door. A chance to point his veritable boat in a new direction.

“I’d never thought about college before,” Abe says. He speaks about college not dismissively, but with a spirited, hopeful tone. QLI clinicians joined him for a visit to the Des Moines-area in the spring, where, at a local college, he enrolled in a degree program for computer-aided design. It was a fresh start that, for Abe, remained entirely in-character. His life and recovery had been defined by his ability to turn ideas into reality. Now, he’d have the chance to make it a career.

“I’ve created things that make my life easier. I always want to find ways to accomplish new goals, and I want to be able to do that for others in similar situations.”

—

As Abe began the final months of his stay at QLI, a six-month sojourn following tremendous chaos and hardship, life came into focus. He had a cutting-edge truck, an accessible home in Waukee, and, with college, the springboard toward a new life.

But one goal remained unaddressed—a return to that original, formative, empowering source of freedom: the kayak.

His QLI team wouldn’t settle for making a kayak trip a one-time emotional salve. Instead, they looked to reconnect Abe to his passion beyond rehabilitation. Their goal was to make kayaking a central pillar of his life, something he could enjoy with relative independence and safety.

Training began in the spring with functional transfers from wheelchair to kayak seat. Then, it evolved into active emergency training, where team members could coach Abe through reliable escape techniques in the event of a capsizing. Alongside these sessions, Abe bolstered his endurance with regular workouts on a mechanical rowing trainer, a stationary resistance-cable machine that simulated the effort of pushing across a lake or down a river bend.

One paddle stroke after the next. Left and right and left again. Measured sweeps, controlled movement. Stronger, better each day.

His training culminated in June, on a clear morning before the sticky summer heat had settled in. Abe, an adaptive sports specialist, and a handful of QLI volunteers gathered at Omaha’s Glenn Cunningham Lake, where they would set out from the lake’s adaptive kayak launch dock. It had been nine months since Abe had been in a kayak. Nine months since he’d been alone on the water.

With only light assistance, Abe transferred into the seat of the kayak. The hull of it thudded down the aluminum ramp into the lake. Then, after the go-ahead from QLI’s adaptive sports specialist, he pushed away from the dock. Far away. Each push of the paddle just a little farther from shore and a little closer to his next chapter. His wheelchair remained behind. Empty, almost imperceptible at distance.

After six months of constant effort, after nearly a year of recovery, he was free.

“It felt good,” Abe says, almost with a laugh. After moving back home and settling back into normal life, he plans to purchase another new kayak of his own, plans on returning to the same rivers he and his brother used to escape from the city. Maybe some new ones, too.

“It feels better now, actually, than it did before. Because now I know. I know the work it took to get me here.”

Here. To a sense of independence, one that wasn’t given or gifted as if by some wish. His is an independence earned. His is an independence he created.