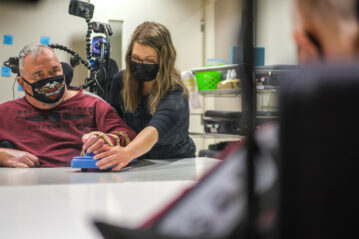

Before they begin their afternoon session, occupational therapist Morgan Chapman gives spinal cord injury rehabilitation participant Terry Fochtmann a once-over. Seated in a powered wheelchair, Fochtmann has piloted as close as possible to the training table in a small therapy room.

Before they begin their afternoon session, occupational therapist Morgan Chapman gives spinal cord injury rehabilitation participant Terry Fochtmann a once-over. Seated in a powered wheelchair, Fochtmann has piloted as close as possible to the training table in a small therapy room.

Chapman eyes her client from head to toe and back again. She gauges his seated posture and uses her hands to adjust the forward roll of his shoulders.

“Posture is crucial in an exercise like this,” she explains. “If someone isn’t seated properly, it becomes harder to perform the functional stuff.”

“Ah, here we go,” Fochtmann says, joking. “The sheriff’s here. Better follow the rules, folks.”

“Someone called me the ‘Hall Monitor’ the other day,” Chapman says. This is an everyday occurrence for her, these quippy sparring sessions. She has a reputation for fixating on detail, and that fixation brings out the best—and, often, the most sarcastic—in her clients.

“I feel like I get unfair sass around here.”

“No, it’s all fair. You’re picky,” Fochtmann retorts. And as if on cue, Chapman guides her client to keep his trunk set against the seatback. The positioning correction isolates the muscles in his upper body—particularly those throughout his arm and shoulder chain, which have special relevance in today’s session.

Chapman withdraws an armskate from a cabinet. It’s a wheeled, ergonomic tool for individuals regaining healthy range of motion and functional strength. Fochtmann slowly manipulates his fingers around the handrest, where his hand rests not-quite-flat on the elevated mount.

Chapman withdraws an armskate from a cabinet. It’s a wheeled, ergonomic tool for individuals regaining healthy range of motion and functional strength. Fochtmann slowly manipulates his fingers around the handrest, where his hand rests not-quite-flat on the elevated mount.

Since his injury, Fochtmann’s arms and hands and individual digits haven’t responded the way they used to. They make sluggish, gentle movements. Those movements lack precision, lack strength. It hurts to stretch his arms too far forward or too widely to any one side. Restrictive tone—an elevated resting state his muscles experience at nearly all times—locks his arm into a 90-degree angle beyond his control.

It is as though his own muscles have rebelled against him, perpetually contracted.

Limitations like these make it difficult for Fochtmann to perform a range of everyday tasks. Even driving his wheelchair, an act that requires a not-insignificant amount of forearm management, isn’t something he can do easily.

But that’s why he’s here today, here with his occupational therapist.

He strains, extending his arm as best he can over the tabletop, where Chapman helps navigate through a routine of gentle stretches. Motions outward and back in toward the body. They train the left arm first. Chapman hopes to activate his tricep, the natural antagonist to his over-engaged bicep. The armskate’s small plastic wheels remove much of the friction that might otherwise prevent someone from generating motion against a flat surface.

For the better part of an hour, the session proceeds with a quiet focus.

For the better part of an hour, the session proceeds with a quiet focus.

“We talk a lot about neuroplasticity,” Chapman says. “But research shows that the spinal cord has similar ability to respond to mass repetition, particularly regarding motor and sensory input. During these exercises, Terry is really consciously thinking about the feeling of firing this isolated muscle.”

They meet for these training sessions multiple times every week, sometimes performing more than 100 repetitions of a given exercise in a single meeting. This is still new territory for Fochtmann’s recovery, an aspect he’s exploring one small breakthrough at a time.

And it is in the pursuit of such breakthroughs where Chapman’s attention to detail matters most.

“What we do doesn’t always look functional,” she says, “but it’s foundational for the skills he’ll end up learning at QLI.”

BUILDING THE BRIDGE

Consider the occupational therapist as you might an engineer.

To blueprint a bridge an engineer applies an array of science-hardened principles. They are problem solvers first and foremost, responsible for ensuring the practicality of a structure yet to exist. They see details few others notice, anticipate shortcomings few others forecast. And, after identifying weaknesses in a structure’s integrity, they establish countermeasures to support the design’s intended function.

This is the role of the occupational therapist. They build the bridge between the foundational and the functional, threading an individual’s physiological gains into the everyday actions that make up their core routines.

This is the role of the occupational therapist. They build the bridge between the foundational and the functional, threading an individual’s physiological gains into the everyday actions that make up their core routines.

“Occupational therapists are trained not only in how the body works and how it may be affected by injuries or illnesses or aging,” Chapman says, “but also in how to modify a task or the environment to allow someone greater independence.”

You likely haven’t thought twice today about the way you hold a fork.

Likewise, it probably wasn’t a conscious, laborious effort to enter the shower this morning or slip on a pair of jeans.

And yet, for someone combating the effects of a severe injury, these feats can’t be achieved on autopilot. They’re elaborate, multi-step processes that suddenly demand inordinate time and exhaustive effort.

It’s here where Chapman and QLI’s team of occupational therapists build efficient pathways to success—through formal therapy training and functional repetition.

RESTORATION, COMPENSATION

Herself a specialist among specialists, Chapman plies her expertise with the men and women who come to QLI following spinal cord injury. She approaches these complex diagnoses hoping to walk the tightrope between restoration and compensation.

“My biggest goal is always to help restore as much function as possible,” Chapman explains. “However, I am constantly thinking about how I can start helping individuals regain a sense of independence to believe in their abilities and potential to achieve.”

In Chapman’s day-to-day therapy appointments, that balance stands out.

One of her current clients, a woman suffering from a rare and debilitating immune disorder known as Guillain-Barré Syndrome, is a case study in constant progress. Early in her recovery from widespread paralysis, the client requires tremendous support.

To promote the restoration of function, Chapman uses regular training sessions to focus on physical improvement. They play a game in which the client uses her arms to bat a small basketball across a mat or a table. When it’s time to hone precise movements and even incorporate finger use, the client works with a tactile shape puzzle, matching small wooden blocks to color coordinated patterns on a sheet.

It’s quite the challenge for someone regaining fine control over their arms.

But small milestones represent important openings. The client demonstrates an ability to independently pronate or supinate her forearm, firing the necessary muscles to flip her hand palm-down or palm-up at will. It proves crucial as they begin training to perform real tasks.

And it is here that compensation creates opportunity.

And it is here that compensation creates opportunity.

Chapman joins the client for breakfast. At this early stage, the woman is not ready to hold a fork with her fingers, but modifications can reduce the difficulty of the task. She wears the fork in a specialized brace-like glove fitted to her hand.

And with the simple addition, using the same muscle groups targeted in therapy, she can eat.

“I’m providing almost minimum assistance today,” Chapman says, cupping her hands under her client’s arm as the woman raises fork to mouth. It takes a moment for the client to coordinate her own movement, and, occasionally, Chapman taps on a part of the woman’s arm, signaling the isolated muscle she wants activated.

The interplay between restoration and compensation is a delicate one. But it allows the occupational therapist to focus on lifelong progress while not delaying immediate accomplishments.

“My ultimate goal is to get rid of the equipment in the long term,” Chapman says.

“But modifications don’t hurt in the short term if it means someone can go into the bathroom and brush their teeth themselves. That may seem small, but it’s huge when you might otherwise be relying on others to do everything for you.”

BEYOND THERAPY

QLI serves a wide range of individuals—not only in the scope of diagnosis, but in the relative distance from injury. Some rehabilitation clients are years into the process of recovery. Others find themselves just weeks removed from a life-altering event, still wrestling with the shock and disbelief of such global change.

Here, therapists weave their practice into emphasis points of each person’s life. It often reaches beyond simple training. A person learning to operate their chair, for instance, might get to practice that skill in a friendly game of wheelchair soccer. Or, if a rehabilitation participant has the ability and the desire to learn to drive a vehicle, QLI’s team can incorporate that into regular sessions when appropriate—as often as the client may request. Without siloed, discrete programs and limiting schedules, occupational therapists like Chapman can focus on genuine impact and tangible skill readiness. Rather than budget time and effort into what’s possible under constraints, QLI’s team has the benefit of involving itself into a given client’s program as much as deemed necessary.

Here, therapists weave their practice into emphasis points of each person’s life. It often reaches beyond simple training. A person learning to operate their chair, for instance, might get to practice that skill in a friendly game of wheelchair soccer. Or, if a rehabilitation participant has the ability and the desire to learn to drive a vehicle, QLI’s team can incorporate that into regular sessions when appropriate—as often as the client may request. Without siloed, discrete programs and limiting schedules, occupational therapists like Chapman can focus on genuine impact and tangible skill readiness. Rather than budget time and effort into what’s possible under constraints, QLI’s team has the benefit of involving itself into a given client’s program as much as deemed necessary.

And when the goal is to rebuild fundamental daily skills, necessary is just the starting point.

Chapman routinely spends dozens of hours every month coming in early to assist with clients’ morning hygiene or dressing routines, or staying late to supervise cooking and dining efforts—all to ensure the repetition is effective and the individual is on a path toward sustained success.

But catastrophic injury takes an emotional toll, as well, one that often shows itself most clearly in the quiet moments, when actions that had previously seemed so minor prove to be so difficult.

“It’s important that I recognize the moments when I need to be more of a coach,” Chapman says. “As an occupational therapist, I want to encourage rehab clients to think ‘How can I?’ To see possibilities instead of being in the mindset of ‘I can’t.’”

Occupational therapy, at its core, isn’t simply a field about managing everyday activity or restorative function. It’s a process of uncovering purpose. Occupational therapists at QLI give rehabilitation clients the ability to pursue that which gives their lives meaning—not only creating competence, but true and unflappable confidence.

Occupational therapy, at its core, isn’t simply a field about managing everyday activity or restorative function. It’s a process of uncovering purpose. Occupational therapists at QLI give rehabilitation clients the ability to pursue that which gives their lives meaning—not only creating competence, but true and unflappable confidence.

“We do a lot of the problem solving for clients when they first arrive,” Chapman says. “But that’s because, in a lot of cases, we have to. My favorite part of anyone’s time at QLI is the moment when they start problem solving for themselves.”

A little more than 36 hours have passed since Chapman met with Terry Fochtmann for the armskate training session. Today, they’re in his on-campus apartment.

Their goal is simple: brush his teeth. Or rather, have him brush his own teeth.

It’s a process. They have to maneuver his powered wheelchair near enough to the sink to reach the faucet handles, not to mention the brush and toothpaste. Chapman is quick to notice the aggressive tone in Fochtmann’s bicep. She suggests focusing on using his shoulder muscles, his tricep, his fingers—which have begun to see increased movement after promising sessions with targeted electrical stimulation.

“Oh, boy,” Fochtmann says, already cutting with the jokes. “What’d I tell you? You’re the sheriff.”

They perform a forward lean. Fochtmann reaches out with his more rigid left arm. And today it’s a success, proof positive that his physical training bears fruit. He successfully closes the distance between himself and the items he needs to reach.

The brush itself is fitted to a small nylon loop. Fochtmann slips his hand through. With it, he can practice this simple act of self-care, something that might otherwise require the help of an aide.

The brush itself is fitted to a small nylon loop. Fochtmann slips his hand through. With it, he can practice this simple act of self-care, something that might otherwise require the help of an aide.

And after some practice with the toothbrush, Fochtmann wears a smile.

“The girls around here,” he says, “they really don’t give you much of a break. But Morgan, I can say, is helping get my arms back to work.”

The moment is independence in microcosm.

Even this achievement has the power to make progress feel real. No longer an abstract notion colored by the grief of loss, but instead something as tangible as a toothbrush—one now confidently within reach.

“Look back on your day. Think of everything you did from the time you woke up until this moment right now,” Chapman says, explaining the importance of her role. “Think of brushing your teeth, going to work, reading a book. Hugging loved one, even. All the things we do on a daily basis intertwine to make us who we are.

“They give us a sense of identity. Occupational therapists are concerned with what those meaningful things are and how that meaning makes you uniquely you.”